Legacy, Shadows, and the Long Arc of Redemption

Roots of a Legacy: The Djojohadikusumo Lineage

To understand Prabowo Subianto, Indonesia’s current president and one of its most polarizing figures, one must first look backward — deep into the roots of his family’s history, where nationalism, intellect, and controversy have long intertwined.

Prabowo is not just a politician forged by ambition; he is the heir to a powerful lineage that helped build Indonesia’s foundations — and also clashed with its first president, Sukarno.

His grandfather, Raden Mas Margono Djojohadikusumo, was a founding father of Indonesia’s economic sovereignty — the founder of Bank Negara Indonesia (BNI), a member of the BPUPKI, and a champion of constitutional governance.

Margono believed in an Indonesia that stood proud and independent, governed by law and guided by prudence — a vision born from the nationalist elite who dreamed of freedom from colonial control, not through chaos, but through institution-building.

His father, Prof. Dr. Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, carried that torch into the turbulent decades that followed independence. Sumitro was one of Indonesia’s brightest economists — educated in the Netherlands, shaped by Keynesian theory, and committed to economic nationalism guided by technocracy. He believed the young republic could rise only through rational planning, industrialization, and disciplined governance.

But ideals have costs. In the 1950s, Sumitro’s pragmatic, technocratic vision clashed with Sukarno’s revolutionary populism and guided democracy.

As Sukarno embraced centralization and ideology, Sumitro warned of fiscal collapse and creeping authoritarianism. When regional dissent in Sumatra and Sulawesi erupted into the PRRI rebellion (1958), Sumitro was accused of being one of its architects.

Branded a traitor, he fled into exile.

Exile and Return: Lessons in Patience and Power

For nearly a decade, Sumitro Djojohadikusumo lived as a man in the wilderness — an economist without a country, teaching abroad while Indonesia’s economy faltered under revolutionary zeal.

His return under Suharto’s New Order marked both personal redemption and ideological vindication. The technocratic, export-led, development-driven policies he once preached became the foundation of Suharto’s economic success.

That experience left deep marks on his family. Young Prabowo saw, firsthand, the fragility of power, the cost of dissent, and the necessity of pragmatism. He learned that vision without strength leads to exile — and that redemption comes only through discipline, patience, and timing.

It is this generational arc — from Margono’s idealism to Sumitro’s exile and restoration — that shaped Prabowo’s conviction that Indonesia must be strong, united, and sovereign, or risk being broken by its own divisions.

Past Shadows: The Soldier’s Burden

Yet for all this intellectual and patriotic heritage, Prabowo’s own past casts a long shadow.

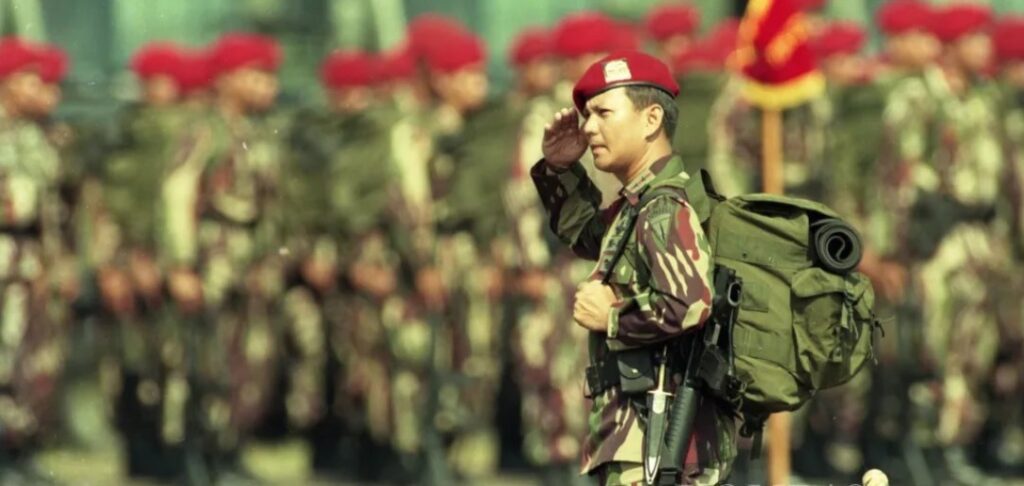

As a young officer rising through the ranks of the Indonesian Army, Prabowo became one of its most capable — and controversial — figures. A graduate of military academies both at home and abroad, he commanded elite forces, led operations in East Timor and Papua, and built a reputation for decisive, uncompromising leadership.

But the twilight of the Suharto era brought tragedy and turmoil. In 1998, as the old order collapsed amid riots and reform, activists disappeared — and Prabowo’s name was linked to their abductions. Though never convicted, he was dismissed from the military and spent years in political wilderness, echoing the exile his father once endured.

To his critics, this is the original sin: the fear that behind his nationalism lies the strongman’s instinct for control. To his supporters, it is the crucible that forged resilience — a man who has stared into the abyss of downfall and learned restraint.

The truth, perhaps, is more complex. Indonesia’s history is filled with leaders who have fallen, returned, and redefined themselves. Prabowo’s story may yet belong to that tradition — if he can transform command into compassion, and discipline into justice.

Present Choices: Technocratic Power, Populist Rhetoric

In recent years, Prabowo has surprised both allies and critics. He accepted defeat gracefully in 2019 and joined President Joko Widodo’s cabinet, serving loyally as Minister of Defense. It was a pragmatic, even humble move — signaling a shift from confrontational populism to cooperative statecraft.

Now, as president, he carries both the promise and the peril of his lineage.

- From Margono, the belief in institutions.

- From Sumitro, the discipline of technocracy.

- From Suharto, the instinct for order and authority.

His agenda — sovereignty in food, energy, and defense; strategic non-alignment; technocratic governance — reflects a coherent vision: a strong Indonesia in a volatile world.

Yet it also stirs unease. His centralized leadership, military influence, and close ties to old elites remind many of the New Order’s grip. His populist-nationalist rhetoric inspires pride — but risks blurring into paternalism.

Indonesia’s democracy, born from Reformasi, watches closely: Can Prabowo’s strength protect liberty — or will it seek to contain it?

The Doubts: Reformasi’s Ghosts

Many Indonesians — especially those who remember 1998 — remain skeptical.

They ask:

- Can a former general accused of human rights abuses safeguard a democracy built on “never again”?

- Can a man steeped in discipline tolerate dissent?

- Can a soldier trained to command learn to listen?

These questions are not cynical. They are guardrails — reminders that democracy in Indonesia was earned through pain. Prabowo’s challenge is not merely to govern effectively — it is to prove morally trustworthy. To show that strength need not become suppression, and that national pride need not silence pluralism.

The Chance to Prove Them Wrong

Every great Indonesian leader has faced a moment of reckoning — a test of whether power serves ego or nation. Prabowo now stands at that threshold.

He has the pedigree of a nation-builder, the experience of a soldier, and the memory of exile. He carries his grandfather’s idealism, his father’s intellect, and his father-in-law’s cautionary tale.

If he can channel his discipline into fairness, his nationalism into inclusivity, and his authority into service, Prabowo may yet complete the arc of redemption begun by his family generations ago.

But if he yields to old instincts — if command replaces dialogue, if strength hardens into fear — then history may judge him not as a redeemer, but as a repetition.

The next chapter of Indonesia’s story will not be written by power alone, but by whether the son of Sumitro and grandson of Margono can lead not just with force — but with faith, wisdom, and humility.

In the end, Prabowo’s greatest battle is not with his critics — but with his own past. And if he wins that one, Indonesia might win with him.